By Luke Powers

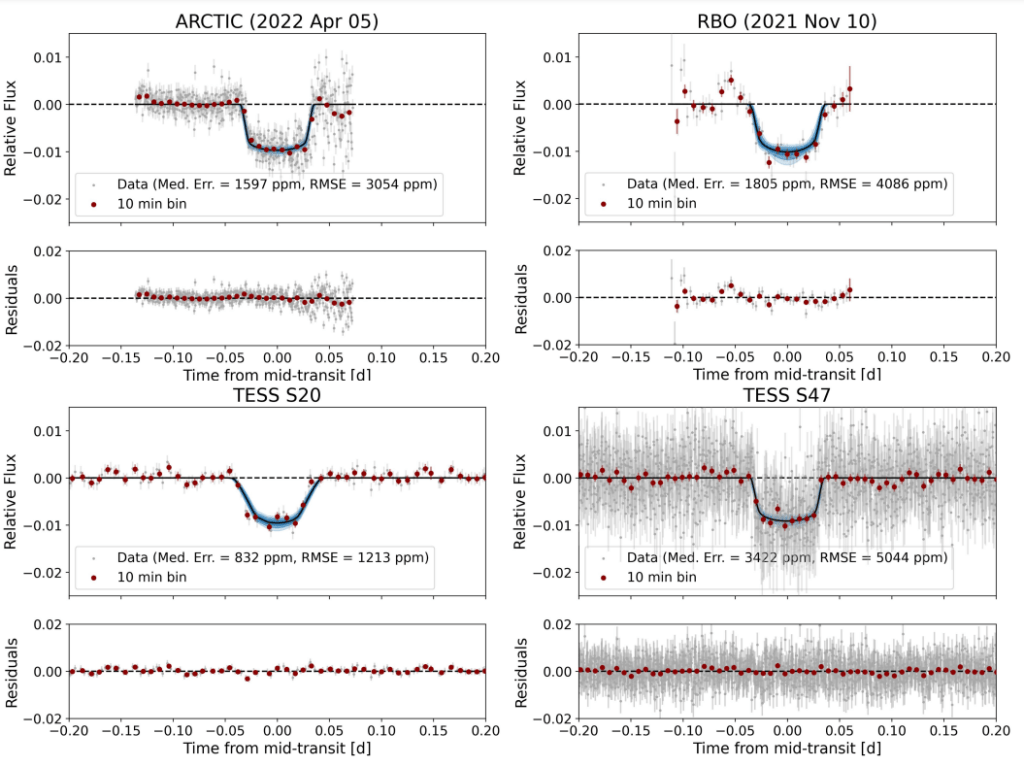

The planet now known as TOI-3785 b was observed in 2019 by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). TESS observed periodic dips in the star’s brightness (known as a transit) that occurred every 4.67 days. As TOI-3785 b moves in its nearly circular orbit, there are predictable times (one orbital period) when this planet will partially obstruct our view of the host star, thus blocking a small percentage of its light. In the case of TOI-3785 b, approximately 1% of the host star’s light was blocked – motivating further investigation of this potential planet. From this photometric transit we could constrain planetary size, leading us to the conclusion that this planet is similar in size to Neptune (Figure 1).

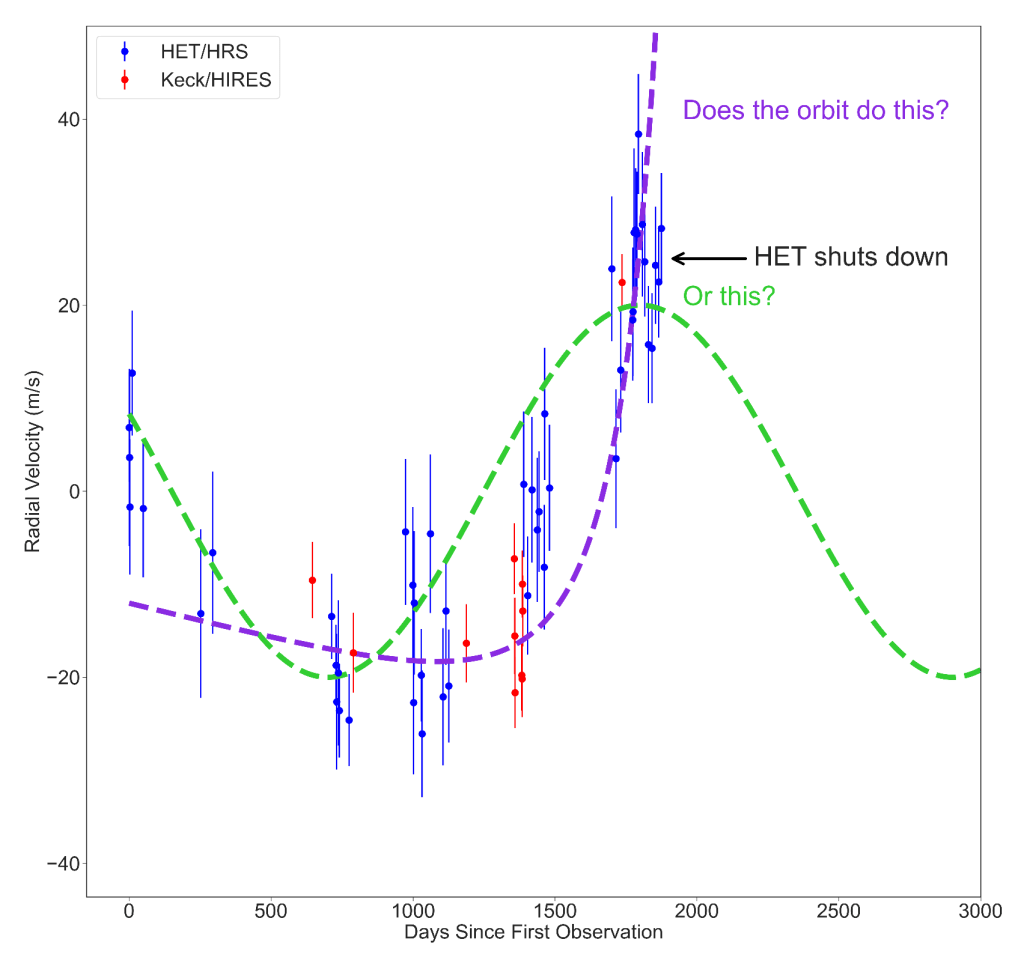

Figure 1: Transit observations of TOI-3785 b with red points showing 10-minute bins. The top row shows individual transits of TOI-3785 b observed with the ARCTIC instrument on the 3.5-meter Apache Point Telescope (left) and with the CCD camera on the 0.6m Red Buttes Observatory Telescope (RBO; right). Bottom row shows the multiple transits observed by TESS in Sector 20 (1800 second exposure time; left) and Sector 47 (120 second exposure time; right) stacked on top of each other. During transit, TOI-3785 b blocks out about 1% of the total light from its host star as it passes in front of it.

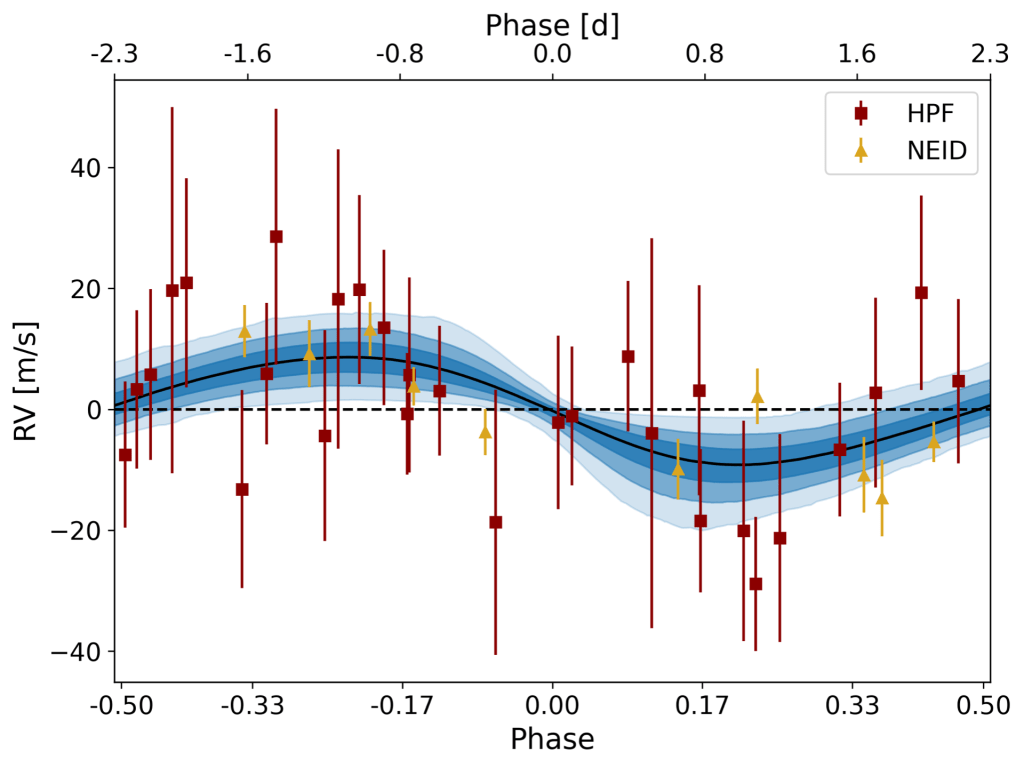

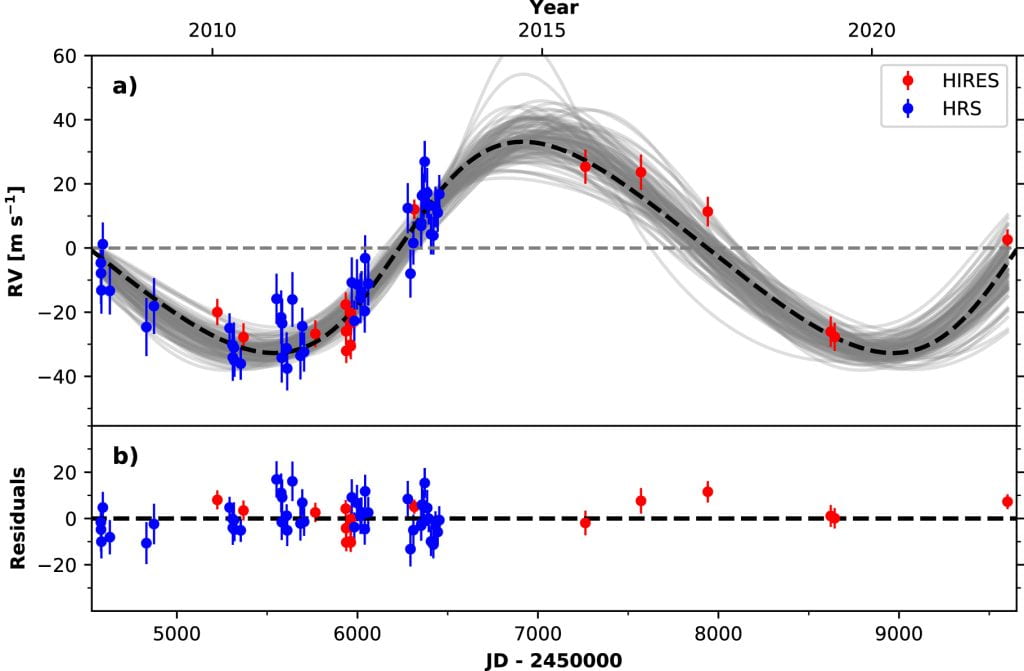

Figure 2: Phase folded radial velocity points from both HPF (dark red) and NEID (gold) with the best fit model plotted in blue along with the 1, 2, and 3 sigma uncertainty contours. As TOI-3785 b orbits, it causes its star, TOI-3785, to move with a speed of 20 m/s towards and away from us.

Even in light of this transit data, a planetary sized object does not necessarily equate to an exoplanet. Further investigations are required to rule out other possibilities such as white dwarfs, brown dwarfs, or eclipsing binary stars – any of which could create a similarly deep transit. Deriving a constraint on this object’s mass is required to rule out other non-planetary objects. Ground-based follow-up of the host star’s radial velocity (motion of the star as it is being tugged around by the object) using the Habitable-zone Planet Finder and NEID spectrographs revealed a surprising mass estimate (Figure 2). This larger-than-Neptune-sized exoplanet only exhibited a mass 80% that of Neptune (15 Earth masses)! This leaves us with a density of 0.61 grams per cubic centimeter, meaning that if this planet were to be submerged in water, it would float!

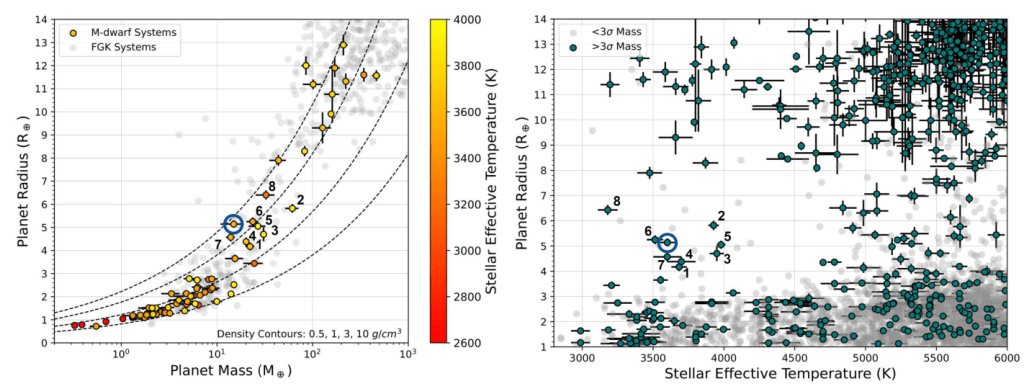

Unique Mass and Radius Reveals an Addition to a Rare Planetary Population

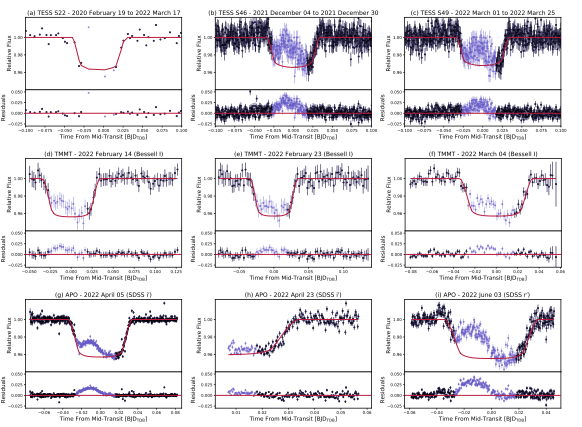

These estimations of the planet’s mass and radius, when viewed in the context of its cool and small M-dwarf host star, show intriguing results (Figure 3). When comparing it to all confirmed exoplanets, a surprising dearth of large planets around cool stars arises – notably when compared to similarly sized planets around hotter stars. In particular, we identify TOI-3785 b as belonging to a rare class of Neptune-like planets that orbit M-dwarf stars, only of which 8 have been confirmed. The discovery of a new planet in this parameter space, especially one with a lower density, has strong implications for our understanding of how gas giant planets form around low-mass and low-temperature stars.

Figure 3: Left: Planet radius plotted against planet mass for all planets with a well-measured mass. Planets orbiting smaller M-dwarfs are denoted with the color of their host star. Planets orbiting larger stars are plotted in gray. TOI-3785 b is circled while all the other known Neptunes orbiting M-dwarfs are numbered. Right: Planetary radius plotted against stellar temperature showing the clear lack of Neptunes around cooler stars.

In our recent paper on the confirmation of this planet, we explore the likely formation pathways rare planets such as TOI-3785 b may have taken. Observing the lack of confirmed Neptune-like planets around cool hosts leads us to question what we are missing about planet formation and/or evolution that leads M-dwarfs not to favor large planet formation. In this publication, we explore a planetary formation model that may be responsible for this Neptune shortage. The most popular and well accepted model for planetary formation is core accretion, in which a dense ring of gas and dust surrounding a star begins to collapse into a single point along an orbital path through the collision of planetesimals. This small collection of mass will begin to accrete heavier material onto its surface, eventually leading to a planet inside of a balanced orbit. In the case of ample material and undisturbed formation time, a planet may continue to grow until a significant size is reached, allowing for accelerated mass accumulation to occur known as runaway accretion. This is a common description of how massive Jupiter-sized planets came to be. In the case of TOI-3785 b, this planet did not achieve the same mass as many gas giants. Why? We proposed that planetary cores fit for accretion on the level of gas giants require much more time to form around M-dwarfs due to the lower mass of their protoplanetary disks. This creates a situation in which these cores do not have sufficient time to grow to their critical mass, and therefore accrete only into mid-ranged Neptune-like planets. This lack of surrounding material may be one possible explanation; another equally plausible explanation is that a core poised for runaway accretion could have been denied sufficient material from a disruption event that caused either disk dispersion or planetary migration to occur. Either scenario would prevent this protoplanet from developing into a Jupiter-mass planet. This suggests that M-dwarf Neptunes may arise from either lack of material or from external disturbances. These rare disturbances that promote mid-ranged planetary formation may be the reason only a handful of M-dwarf Neptunes have been confirmed.

The Neptune Desert and a Need for Caution Concerning M-dwarfs

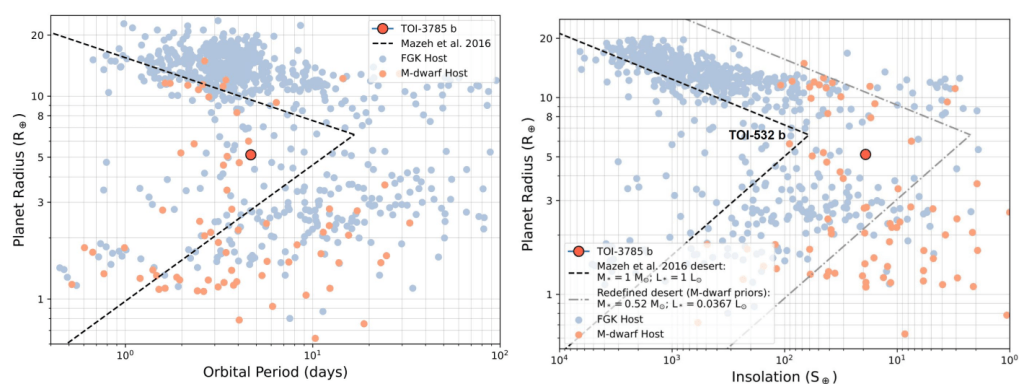

The “Neptune Desert” was first proposed in Mazeh et al. (2016) in their paper Dearth of short-period Neptunian exoplanets: A desert in period-mass and period-radius planes . In this publication they highlight an extreme lack of confirmed exoplanets that exhibit mid-ranged radii (4-7 Earth radii) as well as short orbital periods (< 10 days). This promotes several questions regarding the formation and evolution of these short-period Neptune planets and why this dearth is observed.

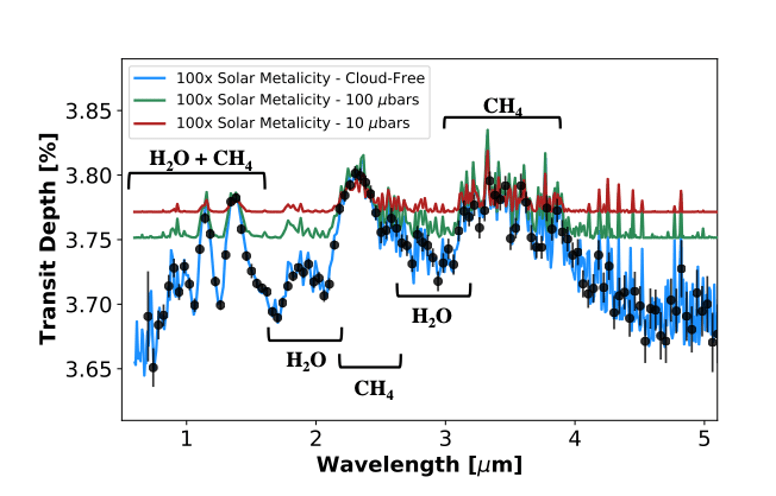

Figure 4: Left: The Neptune Desert reported by Mazeh et al. (2016) in orbital period – planet radius space. The dashed line denotes the defined desert. Red points are planets orbiting M-dwarfs with TOI-3785 labeled. Right: We reorient the Neptune Desert bounds to insolation (light received by the planet) – planet radius space. The dark dashed lines are the redefined Neptune Desert. Since TOI-3785 is a much cooler star, TOI-3785 doesn’t receive as much light even though it has a similar orbital period to many planets orbiting hotter stars. By redefining the Neptune Desert, we show that TOI-3785 b is not in the Neptune Desert. The only M-dwarf planet in the Desert is TOI-532 b.

TOI-3785 b falls within this radius-period space (Figure 4). With a radius of 5.14 Earth radii and a period of 4.67 days, TOI-3785 b is found to exist in the middle of this desert. However, before we celebrate an addition to the Neptune Desert, TOI-3785 b must be viewed not only in the context of its planetary characteristics but its host star’s as well. As mentioned previously, the star TOI-3785 is an M-dwarf, meaning that it possesses a lower mass and cooler temperature compared to other stellar types. The lower mass and luminosity of TOI-3785 presents a problem when placing planetary targets within the Neptune Desert. The lower temperature of TOI-3785 will cause planets of Neptune size to receive less stellar radiation, allowing them to retain their atmospheres and radii at shorter orbital periods. This places short period targets within the Neptune Desert not due to their unique formation pathways, but due to the reduced starlight they receive as a characteristic of their host star’s temperature.

In our publication we highlight the necessity to consider a planet in context of its host star when placing targets inside the Neptune Desert. To quantify this, we reorient the Neptune Desert to Radius-Insolation space. Insolation (the amount of stellar radiation a planet receives) is chosen as it encapsulates both the radiative temperature of a host star as well as a planet’s proximity from its host. In this reoriented desert, we find that TOI-3785 b as well as nearly all other M-dwarf hosted exoplanets are shifted outside this new desert. Moving forward, we encourage caution when placing targets inside the Neptune Desert, as planetary correlations depend upon several crucial variables.

Future Work

Now that the initial work for this planet is complete, we highlight the possibilities of what further investigations could achieve. For example, the most intriguing aspect of this planet is its atmosphere. With a high Transmission Spectroscopy Metric (TSM), we identify TOI-3785 b to be the most promising target for atmospheric follow-up of low temperature M-dwarf planets. Learning more about its atmospheric composition will aid in achieving a better understanding of the formation timeline of Neptune-like exoplanets. With the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) recently coming online, this presents an ideal opportunity to dive into the atmosphere of a rare planet such as this.

You can read more about TOI-3785 b in our recent publication, led by HPF team member Luke Powers.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts